Édouard Manet was no stranger to criticism. In 1864, following the scandal of Déjeuner sur l’Herbe (1863), his latest painting, An Incident in the Bullring, was torn apart by critics for its composition. In response, Manet took a knife to the canvas, severing the dead bullfighter from the lively scene around him. This impulsive act of cutting was a recurring habit for Manet, who would later slash scenes of gypsies, nymphs, and even a portrait of himself and his wife, Suzanne, given to him by Edgar Degas.

Manet and Degas, both from bourgeois families, had become fast friends, united in their desire to revolutionize art. But when Degas discovered Manet had slashed his portrait of the couple—allegedly due to dissatisfaction with Suzanne’s depiction—he was enraged. He returned the gift with a note that read: “Monsieur, I am returning your Plums,” a reference to a still life Manet had given him.

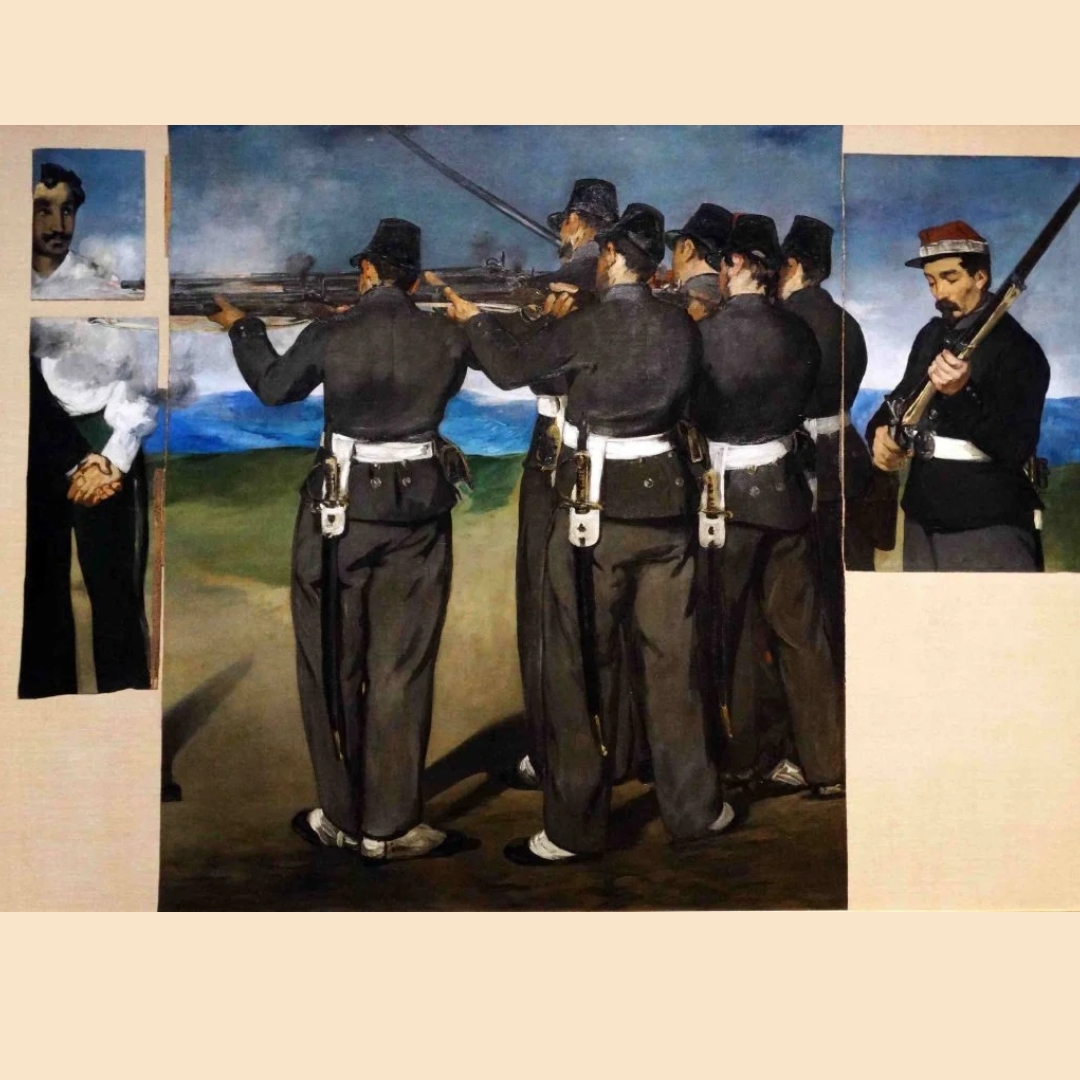

A decade later, Manet revisited The Execution of Maximilian (1867), only to find it damaged. The left side of the painting, which depicted the Mexican emperor Maximilian and his generals, was gone. While it’s unclear if Manet himself cut it, his tendency to alter his canvases makes it likely. After his death in 1883, Manet’s family divided the painting into four parts, selling them off.

Photographs by Fernand Lochard, taken for the estate auction, show the painting intact. But later, the family removed more sections, including the legs of Maximilian’s general and a sergeant. Degas, outraged by the destruction, set about reassembling the fragments, even gluing them onto a new canvas. When the painting was acquired by the National Gallery in 1917, it undid Degas’s restoration, and the fragments were displayed separately for decades.

Today, The Execution of Maximilian is restored—but only in part. The friendship between Manet and Degas, however, never fully healed, though Degas’s act of restoration after Manet’s death remains a rare gesture of posthumous kindness.